Forty-eight Riddles and a Pile of Spice: James Pollock's Durable Goods

"There isn't, of course, anything stopping me from coming back to this space and telling you in 2032 how my sense of coffee grinders has or hasn't been shaped by reading Pollock's poem about them."

Several years ago, I was running a biweekly reading series out of a bar on Dundas St West here in Toronto. The reader that night was my old professor, the grand dame of Newfoundland poetry, Mary Dalton. Mary was killing it in her confident quiet way and had warmed the crowd of Upper Canadian hipsters up to the point of collecting applause between each piece.

Mary was reading from her second Vehicule Press title, Red Ledger, which was old by the time she got there (it was her third Vehicule Book, Hooking, that generated her tour of the West.) She finished by reading selections from a series of riddles. Riddles are a local delicacy in Newfoundland literature, and are second only to the rant among the island’s literary forms. Each riddle is a little metaphor machine, and the leaps Mary did were memorable and keen.

After stringing together a half-dozen riddles Prof. Dalton folded her arms over the book in front of her and said, "Well?" Her applause stopped and the audience looked among itself. She pressed on: "What were the answers to my riddles?"

The receptive crowd struggled, and I don't think it is because they were shy (they were never shy). I suspect it is because the answers, like the answers to most contemporary riddles in English, were actually just too easy and self-apparent; it felt like school to shout out an answer.

The modern riddle suffers a little from what we understand as the purpose of metaphor in this place and time, namely that it is a way to leap to understanding through the leverage of novel objects. A way to turn the novelty of words against themselves, make them mean something to each other in a new way, by highlighting what we understand as their transferable attributes. A very good poet like Mary Dalton is going to get us to our destination with room to spare when she drives us down the highways. Most riddles are easy because we use them to get to their answer; we don’t take them on longer adventures. The modern riddle is task-oriented, and poets have become good at them. The joy of the form is in the development of figurative speech; it’s no longer about getting to an answer. It is a sharing of skill.

The short descriptive poems in James Pollock's Durable Goods are not, it's important to get out of the way, riddles. If they were, they'd do themselves a great disservice by giving away their answers in their titles. But in a deeper way: they are riddles, in that they are also little metaphor machines that generate figurative description.

What Pollock’s poems feature, and why I opened with my boozy memory of the reading by his Vehicule Press stablemate Mary Dalton, is a really complicated and interesting relationship with sense. This is accomplished not at all by powering down the metaphor machine but by sending it on a number of detours and down a few dead ends. They are refreshingly, interestingly, less task-oriented riddles. They’re jaunts; not errands.

Perhaps some examples? In providing them, I'm going to do you the service of removing their titles, so as to present them to you in their true form, the riddle.

Arms folded on the desk. They’re skeptical,

aloof. They have their own way of seeing

things that is slightly off, not magical

exactly, but somehow mind-bending

~

in the way they turn the world, if not to

their will, at least away from the world’s will,

if the world may be said to have one: true

visions, achieved through speculative skill.

And:

This clear pool in which the white winter sun

of a ceiling light appears; cold glacier

meltwater. Then the wan face of someone

haloed peering up at you from under.

~

Long sploosh and the puddle begins to spin,

small mad whirlpool, then disappears, almost,

with a stuttering gurgle. And again

that trembling, holy image of a ghost.

This is fun. Did you solve the riddles? If you really want to check your answers, scroll down to Note #2 in Ephemera at the bottom of this essay for the answers. If you really want, I will do one of you a great favour and take a paper cutter to Pollock's book and lop off its top inch and a half, and send it to you. This will remove all the titles, and also the book's own title and author name from the cover, leaving you with forty-eight riddles and a small pile of spice on the front. It might be it’s ideal form, though a problem for copyright lawyers.

The best poems here are ones that direct and also misdirect. The best poems provide context and description and also something stranger: an eccentricity or a misdirection or an aside, the best poems in the book are unreliable riddles. Both poems above play in the etymology of their subject words, they move between description and human context and avoid digging out too direct a tunnel between you and the answers in the titles I’ve removed. Metaphor can bring more joys than mere realization. A poem is not a map, and reading one is not decoding it.

Despite this higher plane, there are of course still Poetry Tricks. A standard structure in Pollock’s riddles is to delve into the imagistic and then pull out of it at the end into a pithy little truth. Abstract thoughts are exits, as in “Coffee Grinder”, whose back half goes like this:

...one last hard seed starts to reel and twitch

~

About the inverted cone, trying not

To get crushed in the whirling burrs. Turn it off

And there’s a disappointed whine, sad thought

Of loss ending in a gravelly cough.

~

Reach down and snap out the fragrant chamber,

Full to the brim of what we’ll soon be drinking,

And measure out some coarse grains of burnt umber

Mixed with brown madder grounds that smell like thinking.

This format gives the impression of the poems being machines whose product is an idea. You (to butcher a metaphor) grind through an imagistic or descriptive middle and through produces an abstract leap at the end, one that, like any product, follows the logic of the machine but also surprises with its finished self. But Pollock knows the form well enough to know when it becomes too repetitive, so there are all these little variations, like in “Radio”, where the abstract idea is the entrance. An idea is a machine that produces an image.

Has no privacy. You can read its mind

or, rather, hear the voices in its head,

whether muse or madness or the two combined,

the hiss of multicoloured noise or dead

~

silence. Turnabout–since it rings those clear tones

of talk and music in your own hemispheres—

is fair play. Whence it batters the small bones–

forges, with hammer and anvil, in your ears.

My favourite poems in the collection play with telling you more and then play with using language to tell you less. They are better riddles for being purposely imperfect communicators. The best example, both in the sense of being representative and also being my favorite, is “Saw”:

The panel saw on its hook, like a rag of map,

its blade an obtuse triangle of plain,

its serrated edge a sierra. Scrap

of landscape lush with spirits of the slain.

~

It’s skilled at long division and, like the law,

separates what is good from what is true.

That’s the Cartesian wisdom of this old saw

for whom one divided by one is two.

This works at every level Pollock wants to work, and it's not alone among high notes. It sounds gorgeous: expansive and precise and balanced. It says interesting things (it also exits on an idea, like most of its siblings, though my favourite break from the close reading of the object itself is a few lines above this ending, where the saw is compared to the law). It provides visual queues. It's a touch nostalgic. The AB pattern (there in every poem) asserts itself in some lines and is backgrounded in others. Do you like this poem? If you don’t, there’s nothing for you here. It’s the best one to my ear. It’s nearly perfect.

It’s then a little dispiriting that the next poem is so similar, and so nearly perfect in the same way. “Compass” harmonizes with:

This clock for telling space turns your attention

to the way you’re going, which is all it knows.

It can’t point you in the right direction

or make you decide to box the compass rose.

~

Though born as a device for divination,

it never points its finger at true north.

It only tries to tell you, by gyration,

more than what you knew in setting forth.

This is, if you’re wondering, the whole book. The book is forty-eight small well-written poems about common middle-class objects that sometimes give way into short observations about the world beyond the subject, and often those observations are interesting. The net effect will come across to you as either refreshingly epigrammatic or alienatingly superficial. I go back and forth, my appreciation for the poems as individual pieces is greater than how I feel for the book as a whole. My immediate reaction to seeing them all lined up one after another, their tricks made clear through repetition, their stubborn nearsightedness more apparent, was that I wanted to go back to how I felt reading the first one.

One of the limitations of this form is I have to write about Durable Goods a few weeks after first opening it. What I'd like to do is write about it a couple years from now. This is useless to you but more honourable for me. I’m reminded of yet another recurring Vehicule poet, Jason Guriel's, similarly concise, object-obsessed exercises in books like Pure Product and Satisfying Clicking Sound. Those books struck me as well-made but slight on first reading, until I found their images staying with me a lot longer than I expected (the second book's title poem comes to mind even now every time I come upon the relic of an iPod). I am wondering if the same will happen with these exercises, which came to feel a little purposeless as they stacked up like perfect illustrations in a child’s picture dictionary. Despite their misdirection they still share a kind of sameness and I wonder if their eventual effects in my mind will dissolve or be, well, more durable. Will the nagging sense of the them as too stiffly apolitical, too stubborn, too…Tory go away?

I mean apolitical in the sense that James is interested in coffee for the sound a grinder makes and not its role in the international trade system. And that's fine, there are lots of ways to take your coffee, and this is the scope of the exercise as Pollock has drawn it up, and he’s good at it. So what’s my problem? Nothing, except the net effects of this consistent embrace of superficiality are that the poems sometimes feel a touch superficial.

Clearly Pollock (and Guriel, and heck probably Dalton, and who knows maybe even me on some days) would say that realization and music are plenty reward enough. The satisfaction in the poems is entirely within the poems, and that renders their satisfaction mobile, hardy, likely to stay with me across years on the changing earth. These poems have earworm potential. I don’t know now if this will happen but I’d like it if it did.

There isn't, of course, anything stopping me from coming back to this space and telling you in 2032 how my sense of coffee grinders has or hasn't been shaped by reading Pollock's poem about them. Maybe we should do that? A poetry review the way Michael Apted would produce it, like a longitudinal study. Let's do so or forget to.

More immediately concerning is the question, for me the reader, of why, exactly, do I want Pollock's character sketches to have more depth to than they do? They are perfect little dancers, why do I also want them to sing ? What in my history as a reader is making me demand verbs for his book of beautiful nouns and adjectives? Why do I need a world beyond text; text is all I’ve been provided? What exactly is my problem with the specific and the small?

Ephemera

Note 1. I like this cover. We have ourselves a kitchen nightmare: turmeric (I think?) overladen in a measuring spoon on a white background. Stains for days. That standard Vehicule Press David Drummond minimalism. I like this cover and, if I can whisper a soft Canlit heresy here, I don’t always like the Vehicule Press poetry covers. They seem universally beloved but I’m developing some worries. There is a lurking sameness to them: small object centered in a monochromatic background, small object centered on a monochromatic background, small object centered in a monochromatic background, and it’s come dangerously close to that thing that sets my teeth on edge: the overriding house aesthetic.

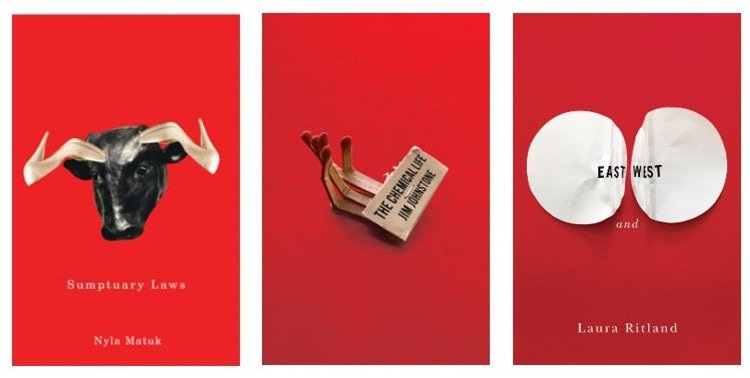

I have a writer’s opinion that cover design, book design in general, should serve to interpret and represent the text and not the press, and the similarity across some of the last few seasons’ titles feels like more the latter than the former. Whether Medrie Prudham’s Little Housewolf (clothespins on white!), or Asa Boxer’s The Mechanical Bird (key on white!) or Nyla Matuk’s Sumptuary Laws (bull’s head on red!) or Jim Johnstone’s The Chemical Life (matches on red!), these feel more and more like objects painted in house colours rather than expressive faces for the texts themselves. I understand lots of publishing operations do this but I tend to want to excuse those doing reprints (the NYRB et al) and have always been made a touch tense by first-pass publishers with such a strong and consistent “look.” It feels like someone has fit these books for a uniform. And yes, this is a not-uncommon way for a press to sort itself out in the market, it’s very common in Europe, etc etc. I get all that and continue to feel slightly squeamish when books from a given press all start to strike the same pose. I’m an authorial-primacy type in certain ways, I guess.

When you play the hits.

My favourite Vehicule Press covers are the ones that keep the simplicity but lose the negative space, like Jim Johnstone’s Infinity Network or this fun yellow pile for Durable Goods. Once you take the note that minimalism doesn’t need to mean great deals of negative space, you have so much more palette to use, and the covers can maintain an intellectual preference for simplicity without feeling all the same.

I am not an aesthete; I’m wearing a baseball cap as I type this, you don’t need to listen to me. But the directionality of cover design has always been of concern to me: does it represent the Press to the book or the book to the world? Durable Goods feels represented to the world here, and I’m not always sure with these covers.

Note 2. You are a nerd and I’m not telling you. Buy the book.

Note 3. I lost my copy of Red Ledger by Mary Dalton in a move. Do you have one? Email me photos of the riddles and I’ll quote one here. Mcarthurmooney at the email service offered by The Alphabet Corporation. Thanks.

Thank you so much for this thoughtful and interesting response to Durable Goods, Jacob. I absolutely agree with you that the riddle is the foundation of the Dinggedicht tradition I was working in here. Nicely done. Here's to ear worm potential!

Thank you so much for this thoughtful and interesting response to Durable Goods, Jacob. I absolutely agree with you that the riddle is the foundation of the Dinggedicht tradition I was working in here. Nicely done. Here's to ear worm potential!